Reflections on the dissertation, one year in

This blog, a reflection on my dissertation project one year into the process, was originally produced as a talk for the 2016 Futures of American Studies Institute. It includes an overview of my dissertation (a snapshot of how I’m concurrently conceptualizing it, though it continues to evolve), some more specific work from the chapter on Audre Lorde’s pedagogy, and then a sense of where I think I’m heading as I move into the next chapter on Toni Cade Bambara.

Overview

My dissertation is tentatively titled, “The Promise of Aesthetic Education: On Pedagogy, Praxis, and Social Justice.” In it, I analyze the intersectional feminist pedagogies of activists, authors, and educators in order to explore what teaching literature can do to produce a more just, equitable, and pleasurable future. Specifically, I’m looking at the formal and informal pedagogies of Adrienne Rich, Audre Lorde, June Jordan, and Toni Cade Bambara, all of whom taught during Open Admissions (1970-1976) and in the SEEK educational opportunity program at the City University of New York. These initiatives sought to make higher education more accessible to the city’s working-class black and Latino students. While I’m interested in what these unique initiatives made possible, I am perhaps even more curious about how these decolonial, antiracist, feminist, and queer pedagogies emerged in relation to many other efforts to materialize social justice nationwide. (So, for instance, this work has led me to become increasingly interested in the pedagogies of the Black Panther Party, the Black Arts Movement, and various freedom and experimental schools.)

The work of these activist authors and educators consistently challenges us to imagine education beyond neoliberal narratives and to think about pedagogy in relation to social change. It encourages us to ask difficult questions such as, how liberatory can education be in a carceral, racial state? What can education do to materialize social justice, not just pay lip service to “diversity” and “multiculturalism” but be part of the downwardly redistributive revolution we so desperately need? In these times of manufactured scarcity and austerity, how can we develop practices to counter the everyday pedagogies of structural violence and dispossession?

This project emerged from the experience of teaching at Queens College, and a realization that all of the questions I wanted to ask about material distribution, structures of injustice and inequality, and cultures of oppression were present and palpable in the classroom. I was also, at the time, involved in an informal, experimental pop-up style university that emerged from Occupy Wall Street, and thinking a lot about the kinds of education this enabled, but also its shortcomings: namely, the reasons why one might need and want institutional structures and resources.

Beyond the pedagogies of neoliberal racial capitalism

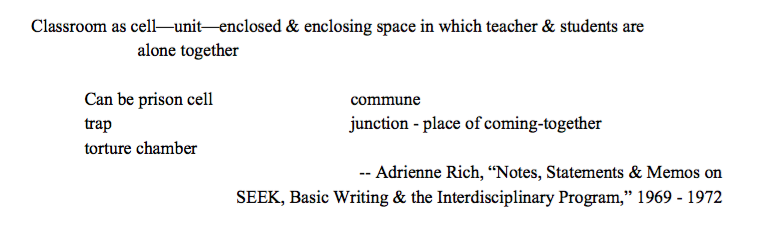

In this poetic, pedagogical fragments, the classroom is described as a space of enclosure: of privatization, dispossession, and carcerality, which contrasts sharply with dominant liberal narratives about education as Enlightenment, and the individual’s progress towards autonomy. Here, Rich concisely reflects the history of education as a mechanism of enclosure: as a means to facilitate the trickle-up economics of racial capitalism. In contrast to carceral environments like the liberal racial state, in which powerful, affluent individuals make decisions for others, Rich reimagines the classroom as a potential “commune” in which students define, rather than merely follow, the rules. As such, it is a place in which everyone participates in governance: in addressing who gets to make decisions for whom, how resources are distributed, and how a given group of individuals can best live together and flourish. While prisons seek to adjust the individuals whose desires are out of sync with the world, Rich suggests that the classroom might allow us to interrogate, and perform alternatives to, the world that is out of sync with our desires.

When Rich authored this fragment, around 1970, she was teaching at City College in the SEEK program, a context in which education was understood as proliferating collective, rather than individual, potential. There, she taught alongside many decolonial, feminist, antiracist, and LGBTQ activist educators, including those who I’ve chosen for my project: Audre Lorde, June Jordan, and Toni Cade Bambara. Here, I’ve provided a few of the quotes that led me to believe that these four figures would help me think about pedagogy, aesthetics, and social justice, and that it would be generative to place them in conversation with one another.

You’ll notice how in the Lorde quote, the open admissions classroom is directly posited as an alternative to conditions of racialized police violence; how in Bambara’s quote, she vehemently refutes any notion that the classroom could or should ever be something like a safe space; and how Jordan’s pedagogy is predicated not on relationships of identification, but of the desirability of difference, while avoiding being merely a multicultural celebration of equality in diversity. As I hope these examples illustrate, the pedagogies I’m tracing are not in the past, but are modes of responding to the long, ongoing neo/liberal moment we continue to inhabit. Indeed, these four figures use women of color feminist and queer of color critical perspectives to theorize the classroom, which may help us reframe contemporary and interrelated debates over the school-to-prison pipeline, trigger warnings, safe spaces, and abstract celebrations of diversity that often obscure conditions of institutional racism and sexism.

Critical context

While these authors have shaped contemporary understandings of feminism, antiracism, and queer theory, their work as educators is rarely acknowledged. By analyzing their pedagogies, we can better understand both their literary texts and their multifaceted attempts to make political interventions, in all domains of their work.

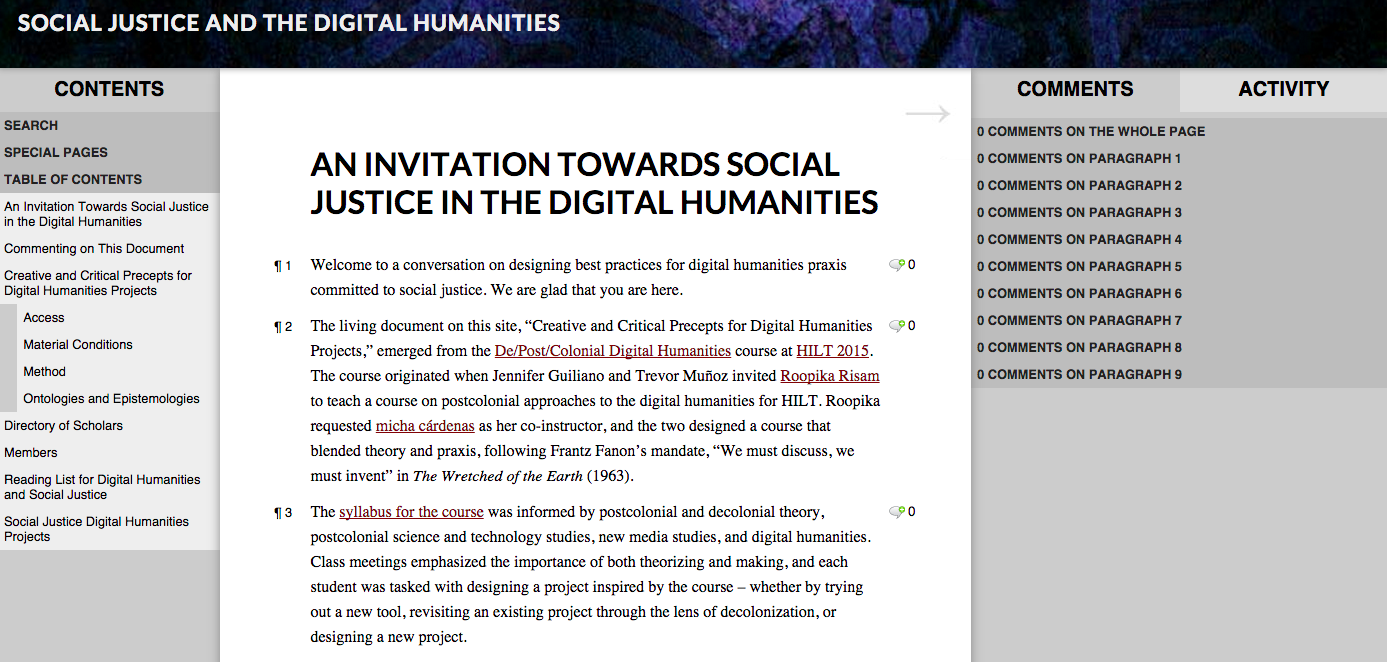

These experimental pedagogies, I hope, will help us proliferate alternatives to the dominant neoliberal ways in which we continue to conceptualize education, particularly as an individual, rather than collective, public, social, and political undertaking. As such, I locate this project at the intersection of several intellectual and scholarly conversations. In one register, this work is in conversation with thinkers such as Paulo Freire, bell hooks, and M. Jacqui Alexander, as it explores how pedagogy functions as a mode of resistance to neoliberalism, and the centrality of pedagogy to genealogies of women of color feminism and queer of color critique. In particular, I emphasize how the praxis emerging from literary and cultural text may offer generative possibilities for critical pedagogy, so that we can think more deeply about both the critical and creative work of education: namely, the alternative, oppositional, and better worlds we can perform and produce in spaces of learning. Samuel Delany, Jose Muñoz, and Sarah Ahmed are key interlocutors in this regard; they have helped me think about the queer utopian possibilities of spaces–how spaces can contour dangerous, pleasurable, and potentially transformative encounters. This project is also in conversation with recent scholarship by Jodi Melamed and Roderick Ferguson, both of whom have illustrated the urgency of rethinking what literary studies can do to address the institutional management and depoliticization of difference and minoritarian knowledges. For those working in the neoliberal academy, but who wish to contest its very conditions of possibility, I’m hoping to elaborate collective, rather than individualistic, modes of literary studies that engage structural critique, interrogate the status quo, and can catalyze social change. Urban education scholarship has been particularly useful in this regard. While this work is rarely routed through the literary, and tends to employ social scientific methodologies, scholars like Michelle Fine, Jean Anyon, and Steve Brier have produced some of the most incisive critiques of neoliberal education, and have been the most bold in exploring collective, participatory, and socially just alternatives.

The promise of pedagogy

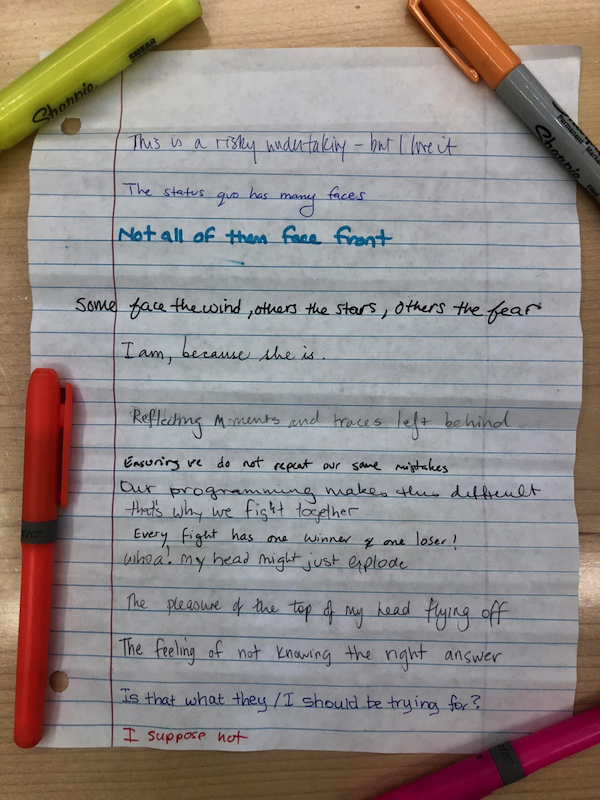

I’ve been thinking recently about why pedagogy is so urgent to my work. Pedagogy, I contend, can be found not only in formal teaching materials like syllabi, lesson plans, and assignments, but also in art, and so for this project I’ve been analyzing the archival teaching materials of these artist-activist-educators alongside their poetry, prose, fiction, films, and essays. I keep returning to the idea that there is something inherently optimistic about pedagogy, but that doesn’t necessarily feel cruel. Thinking pedagogically allows us to act as if things could be otherwise, despite or against all evidence to the contrary. So, through engagements with intersectional feminist literature, I examine how pedagogy holds out the promise that we might intervene in, or at least contend with, the social, political, and economic conditions that often feel out of our control. Indeed, part of what I’m doing is tracing how these artists, authors, and educators address our everyday participation in structures of injustice and inequality and theorize pedagogy as a means of social interruption.

“aesthetics of the outsider”: Audre Lorde and the Praxis of Worldmaking

This excerpt is from the introduction to my first chapter on Audre Lorde’s pedagogy, followed by a sketch of the remainder of the chapter, and some of the questions I’m still working to address. Overall, the chapter explores how poetry and pedagogy were means through which Lorde worked to transform established understandings of art, learning, and politics through the needs and desires of those historically and unequally marginalized by the social order.

—

While contemporary scholars and educators tend to divide critical and creative work, teaching and scholarship, and activism and education, for Audre Lorde, all of these were intertwined. Although she began writing poetry long before she started teaching, it wasn’t until her first formal teaching experience at Tougaloo College that she realized the collective power of poetry: that it could be not only a private pleasure, but a means of doing transformative work in the world. Poems, she argues, are “learning devices,” acts of “teaching–touching–really touching another human being,” imagining the transformations catalyzed by poetry through physical acts of grasping, reaching, and colliding.[1] Following that first experience at Tougaloo and throughout the remainder of her life, the kinds of work Lorde was doing in her poetry–mapping the contemporary conditions of apocalypse, drawing our attention to collective possibilities for social interruption, and imagining pleasure where it had previously been ignored–she was also taking up through pedagogy.

Lorde theorized pedagogical praxis through the discourse of aesthetic education–literally, an education of the senses–learning to touch, listen, and look in new ways. Her praxis dramatizes how both poetry and pedagogy are forms of reaching out, of “touching,” and in touching, realizing that we are not and cannot ever know “another human being.” This idea of touching, rather than peering inside and knowing, or empathizing with others signals an alternative to liberal notions of why and how we should study literature. As such, Lorde’s work has helped me think in more nuanced terms about Jodi Melamed’s argument that dominant modes of liberal, multicultural pedagogy dematerialize antiracism by teaching privileged white students to “know” difference–an argument that I am very compelled by, but also want to explore alternatives to. As Lorde’s praxis indicates, literary studies can do other things. Her work in particular complicates this paradigm by recognizing the incommensurability of lives and experiences, rejecting the possibility of both intersubjectivity and the knowability of the other.[2] If we live and work under the assumption that there are always gaps in our knowledge of ourselves, others, and the world, that we are always missing a part of the picture, then collaborative, dialogic acts such as writing, teaching, and organizing emerge as necessary modes of praxis through which something else–something other than the status quo–might emerge. The subject of this pedagogical praxis, if there is one, is not the discrete individual, but the intimate touch, the spark, the collision, the encounter, that aesthetic and pedagogical experiences catalyze. What I’m interested in is how Lorde taught others to understand this intimate encounter in relation to the social, political, and economic fabric in which we are embedded.

———–

In this chapter, I tune into the generative force of pleasure in pedagogies of social justice: how dynamics of desire are entangled with acts of resistance and refusal, and how we might use such entanglements to “queer” dominant ways of thinking about education. This work is animated by several inclinations. First, I have a hunch that Lorde, like many educators, activists, and artists, was also an educational theorist who can teach us something about pedagogy in relation to neoliberal racial capitalism. While some of these insights emerge in the places we might expect such as her teaching materials and writings about education, other ideas are embedded in the subversive spaces, silences, and estrangements–the literariness, or poetics–of her poetry and prose. Because the status quo is reproduced through the regulation of common sense, certain aspects of social justice pedagogy may emerge through that which is deemed an irrational and expendable “luxury.” Second, I want to develop a method for thinking about the pedagogies of social justice that crystallize through the figure of Lorde, rather than the pedagogy that belonged to her. Doing so is crucial for understanding pedagogy as an inherently collective and unwieldy mode of resistance, and for not reproducing the individualism, partially inherited through legacies of the liberal arts, that shaped (and still shapes) the neoliberal mess we inhabit. Related is my desire not to tell the history of “what really happened,” but to craft a genealogy, or maybe a grammar, of pedagogical praxis that can illuminate the present.

In the first section of the chapter, “A genealogy of danger,” I read Lorde’s poem “blackstudies,” authored during her time teaching at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, as a commentary on the dangers and possibilities of pedagogy in relation to long ongoing conditions of racialized violence, exemplified here by the 1973 murder of a black ten-year old child, Clifford Glover by a white police officer, Thomas Shea. Not only did Glover’s murder and Shea’s exoneration dramatically influence Lorde’s poetry, it also had a profound impact on her pedagogy: her ideas about what to teach and how to teach it. In this first section, I trace Lorde’s calls for a confrontational and riotous education that would manifest dissatisfaction and dissent towards the status quo, placing this pedagogy in a much longer genealogy, through which black studies has been understood as a threat to U.S. liberal democracy. In the sections that follow, I give texture to this confrontational, riotous, and collective education of dissent.

The second section “Teaching at the end of the world” explores how several of Lorde’s lyric poems dramatize the dominant pedagogies of neoliberal New York City: the paths, possibilities, and ways of being and knowing incentivized by cultures of upward redistribution and a present in which crisis is not extraordinary, but ordinary, woven into the fabric of everyday life. I read two of these poems as cartographies of desire, shaped by the material, sensual, and embodied experience of what it feels like to have to share a world–New York City, America–with dangerous, desirable, and unknowable other people. This context illuminates Lorde’s praxis as an effort to unlearn the dominant pedagogies of austerity, privatization, liberalism, and possessive individualism. While education is typically narrated as the individual’s journey towards autonomy, two of Lorde’s poems, “Teacher” and “Dear Toni” reconfigure learning through its material conditions of possibility, directing our attention to food and mothers, and reimagining education as the process of coming-to-consciousness of our dependency. Drawing on recent work by Grace Hong, I explore how Lorde’s attention to labor and material conditions of possibility urges us to consider how worldmaking is always collaborative, but uneven, and erased through liberal notions of individualism. These poems exemplify her poetic and pedagogical praxis, which involved looking beneath, beyond, and beside the present to the labor, exploitation, and suffering that the status quo actively works to obscure.

One thing I’m continuing to work on in this section is figuring out what is at stake in thinking pedagogically about the lyric poem; to ask what lyric poetry allows for, that narrative can’t capture. So far, I’ve come up with several possible, interrelated ways of thinking about this, though I’m still working through the precise nature of many of these connections. When thinking about lyric pedagogy, I keep returning to Paulo Freire’s critique of the banking model of education, which he emphasizes is predicated on the teacher as narrator who “leads the students to memorize mechanically the narrated content.” And in fact, Lorde’s pedagogical poems were penned at the same moment in which Freire argued that education was suffering from “narration sickness” (1968/1970). Narrative understandings of education, I think, are related to modernity’s teleology of progress and the idea of human perfectibility, but I’m still working to better flesh out this connection. One avenue of inquiry that may help me get there is thinking about the relationship between bildung as the exemplary educational paradigm of modernity and its corresponding literary genre, the bildungsroman–so I’m trying to think about how Lorde’s lyric poetry refutes, complicates, or models an alternative to these. In addition, I’m interested in how Lorde uses lyric poetry, a classical genre understood through its association with the “I,” and the self, towards a different, more collective end.

In the third section of this chapter, “the intimacy of scrutiny,” I trace the collective ways of being, knowing, and relating that emerge through Lorde’s pedagogical praxis. In particular, I illustrate how her famous talk, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” shaped and was shaped by the scene of teaching and learning. Not only did teaching help provide the material conditions of possibility for its articulation, the essay can also be read as a blueprint for a queer pedagogy, in which the classroom is used to explore the materiality of difference and intimate ways of working together that don’t rely on identification with, or the knowability of, others. Read through a pedagogical lens and alongside the additional insights of Lorde’s students, gleaned from her archival teaching materials, “The Master’s Tools,” helps bring into relief a version of aesthetic education in which the texts we read and our reactions, interactions, and conversations tell us less about ourselves as discrete individuals, and more about the social, political, and economic fabric in which we are embedded.

The chapter concludes with a discussion of “Collaboration in the archives”: the ways in which the physical materials in Lorde’s teaching archive embed her praxis in a much larger milieu of activist educators, which is useful, I think, for two reasons. First, it allows us to acknowledge, rather than ignore, the students, colleagues, and administrators who labor to produce the scene of teaching and learning. And second, placing her praxis as one node, intersection, or confluence in a much larger project may help us recognize that there are alternatives to the status quo being explored everywhere, in innumerable, though oftentimes hidden spaces, places, and interactions.

Onward

As I move into the chapter on Toni Cade Bambara, I am thinking a lot about Lorde’s poem “Dear Toni…” (1971) which is addressed to Bambara, and mentions the time in which they were both teaching at City College.

In the excerpt, Lorde imagines encountering Bambara in her office “studying” term papers, imagined here as “maps.” In a document Bambara wrote about teaching in the experimental SEEK program in 1968, she describes how, for their final term papers, students were asked to “design a course that they would like, that would fulfill their needs,” and then during the summer program, they used these ideal courses and “mapped” what they would study together. The summer course that the students ended up designing from the “maps” Bambara studies in this poem was on Colonialism, Neo-Colonialism, and Liberation. I believe that we can read these term papers, and the pedagogical praxis in which they are embedded, as maps to different configurations of power and knowledge: as blueprints for institutions not for a wealthy minority, but crafted around the needs and desires of working-class students. Moreover, I’m hoping to place this pedagogical praxis in the context of the movement for the community control of schools in NYC (1966 – 1970), and to explore how community control inspired pedagogies that extended far beyond its formal end.

In the Bambara chapter, I’m hoping to show how “mapping” was more than just a metaphor for pedagogy; drawing on Katherine McKittrick’s work on black feminist geographies, I want to explore the centrality of placemaking to pedagogical praxis. By reading Bambara’s teaching materials alongside her 1980 novel The Salt Eaters and her documentary on the 1985 bombing of the MOVE organization in Philadelphia, I hope to trace a pedagogical praxis organized around the decolonization of space and sense.

Works Cited

[1] Audre Lorde, “Poet as Teacher–Human as Poet–Teacher as Human” in I am Your Sister: Collected and Unpublished Writings of Audre Lorde, (New York: Oxford, 2009. Ed. Rudolph P. Byrd, 182.

[2] Here, I am thinking alongside Jean-Luc Nancy about the incommensurability of touch, how closeness emphasizes distance, how “the law of touching is separation” On Being Singular Plural, 5 -6.