Interview: Feminism, Activism, and the Digital Humanities

Interview by Rebekah Jo Aycock

I had the pleasure of interviewing Dr. Danica Savonick over the phone on May 18, 2020. I am grateful for her time and energy towards this project and especially appreciate the opportunity to elevate her important insights about the transformative power and potential risks of using digital technologies in the classroom. As the pandemic ravages on, her considerations here remain all too relevant as teachers continue to adapt to the online classroom while working to equip students with the critical thinking skills necessary to grapple with this historical moment.

Rebekah Aycock: How did you come into the field of digital humanities?

Danica Savonick: Well, I think like a lot of us I came into the field indirectly.

In 2012, when I began grad school, I was involved in some organizing, especially organizations coming out of the Occupy Wall Street movement. With Occupy Sandy we were trying to help out in the aftermath of the hurricane that had devastated the city and we were trying to get resources to people who needed them. I was also involved with the Free University of New York City where we would host pop-up universities throughout the city, and professors from Columbia, NYU, CUNY, The New School, and Rutgers would come and hold their classes outside in these parks alongside activists and local community organizers who taught workshops and skillshares. With this organizing, I was interested in the behind-the-scenes ways that we were using technology. I worked with the website and social media and became interested in the power of platforms to get the word out and spread awareness about things, and also how tools allowed us to collaborate on large projects. Through these activist efforts, we used technology to bring people together, share resources, and support marginalized communities. I became interested in how technologies can be used to do good in society.

I also pursued a PhD at the CUNY Graduate Center where there was a lively digital humanities community. The majority of the DH I was exposed to was people using technology for activist purposes, and to support pedagogy, students, and advocacy for marginalized communities. I was really excited by Cathy Davidson’s arrival at CUNY. She brought HASTAC and started the Futures Initiative, programs dedicated to equity and innovation in higher education. So it wasn’t necessarily the kind of distance-reading version of the digital humanities, it was exploring how we can use technology in service to social change.

The last key moment that I’ll mention was that I went to a summer HILT workshop (Humanities Intensive Learning and Teaching) organized by Roopika Risam and micha cárdenas on de/postcolonial digital humanities. That gave me broader exposure to these activist traditions of digital humanities – people who were using technology to do feminist, anti-racist, queer, post-colonial research.

RA: How did being involved with the HASTAC community contribute to your graduate education and now your career?

DS: HASTAC changed everything. There’s no way I would be where I am today were it not for HASTAC. I started as a HASTAC scholar, writing blog posts, contributing to collections like The Pedagogy Project, and attending HASTAC conferences.

Participating in this kind of online scholarly community raised new questions for me. How does a blog post differ from a peer-reviewed journal article? How can we write about complex research in a way that is exciting and engaging and will keep someone wanting to read even if they are exhausted after a long day of teaching? For decades, famous feminists like Gloria Anzaldúa, Audre Lorde, and Toni Cade Bambara have been urging readers, writers, and publishers to consider the material conditions that underscore reading, writing, thinking, and teaching. Readers might work multiple jobs, maybe they have a family, maybe they can only read for a few minutes here and there. All of that is to say that HASTAC has taught me a lot about audience.

HASTAC also gave me the sense that my research was in conversation with audiences beyond my graduate program and even beyond my discipline. This interdisciplinary audience forces you not to use jargon and also to try to provide vivid, tangible examples to support your points. Writing is kind of like teaching in that sense, right? Students aren’t going to believe something is true because you say it, you have to provide them compelling evidence and examples without jargon.

________________________________________________________________________

“…when students have a sense that their words are going to be read by someone beyond the classroom, that a student in another college classroom might be reading it, then it’s going to actually have an impact and they’re more motivated to create something that they are proud of and that they care about.”

________________________________________________________________________

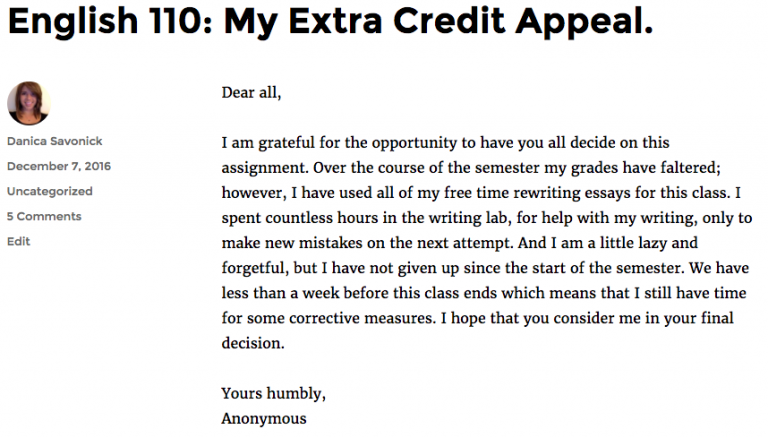

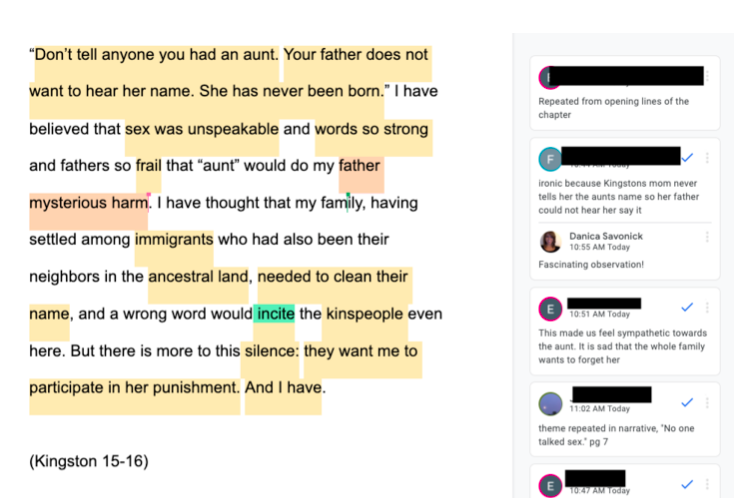

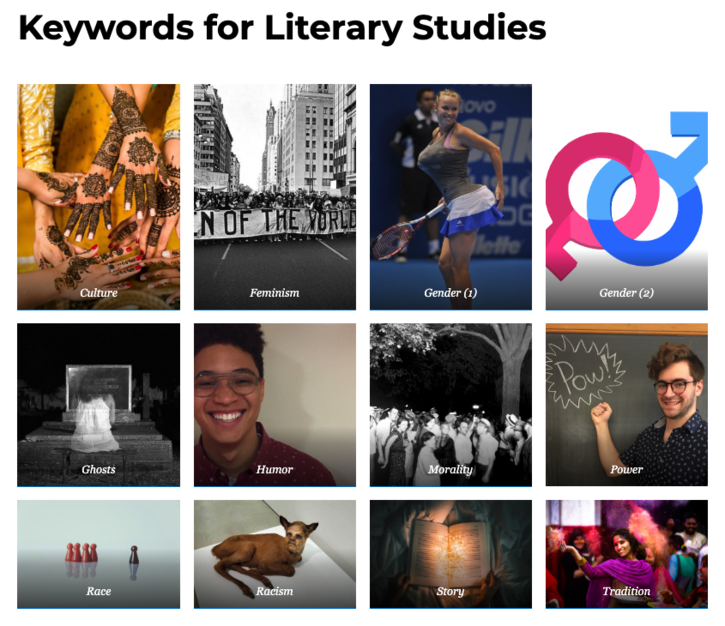

HASTAC also impacted my teaching. Every semester now my courses conclude not with a final paper that’s submitted only to me but with some kind of public project or blog post that can be read by audiences beyond our classroom. Sometimes this takes the form of an actual post on HASTAC. Stephen Berg, a member of the HASTAC community, created a group called Scholarly Voices within HASTAC to showcase undergraduate writing. Students can read the work of other undergraduates and then write their own post for that group. I’ve been so excited by the ways that these kinds of public writing assignments increase the quality of student writing. Sometimes when students are only submitting something for the professor it can feel tedious, like, “Why are you torturing me? Why are you making me revise these sentences over and over and over again?” But when students have a sense that their words are going to be read by someone beyond the classroom, that a student in another college classroom might be reading it, then it’s going to actually have an impact and they’re more motivated to create something that they are proud of and that they care about.

HASTAC has also taught me about the importance of networks and communities. I came to realize that for those of us who are interested in teaching and social change, part of that activism is sharing what has worked well for us in our own classrooms so that other people in other classrooms and contexts can learn them and build off of that.

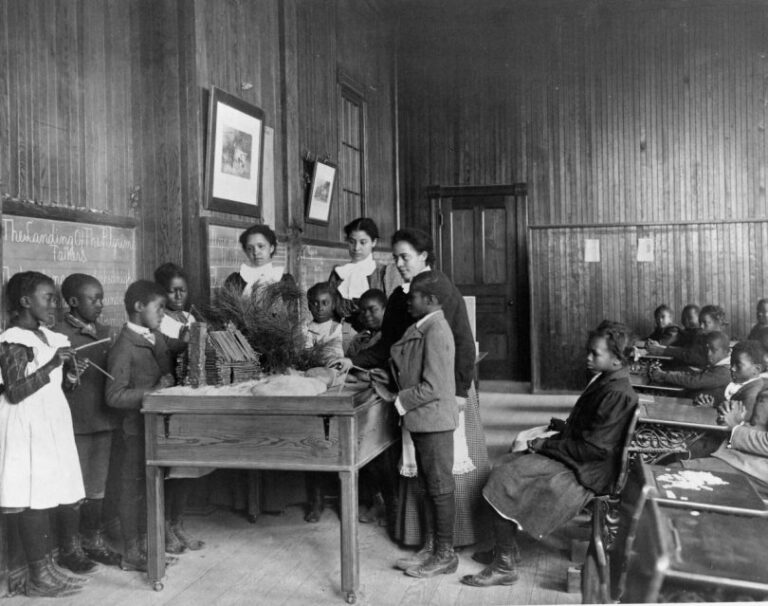

It’s interesting how a contemporary online network like HASTAC has shaped my archival and historical research on feminist pedagogy. For decades, scholars, activists, and teachers have created these kinds of teaching communities and shared resources, syllabi, lesson plans, and assignments. They’ve reflected on their teaching and written about what works, as well as other failures and missteps along the way. My research only goes back to the 60s and 70s – I’m sure you could find activist communities going much farther back than that.

Read the full post on HASTAC