I first read Toni Morrison in a college literature class on “Experimental Lives.” In this course we traced the will to experiment across novels like Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, Paul Bowles’ The Sheltering Sky and Michael Ondaatje’s The English Patient. At that time, many of us college students were living away from our parents for the first time, figuring out what we wanted our lives to look like and how we wanted to be in the world. And the protagonists of these novels gave us models for an unconventional life. Did we want to be artists of the self, traveling cross-country, intoxicated by language and life, in exuberant protest against societal constraints like Dean and Sal, the protagonists of On the Road? Or did we want to retreat from a world ravaged by unfathomable human atrocity and violence, forming intimate communities of care amidst the ruins, like the characters in The English Patient? But then we read Toni Morrison’s Sula, and that changed everything.

Sula traces the paths and possibilities available to four Black women living in Medallion, Ohio in the mid-twentieth century. Gradually, we learn the stories of the women in two families—the Peace family and the Wright family—which crystallize in a friendship between the youngest girls in each: Sula and Nel.

“Hannah, Nel, Eva, Sula were points of a cross,” Morrison writes, “each one a choice for characters bound by gender and race… a merging of responsibility and liberty difficult to reach” (xiv).

In the style characteristic of her writing, Morrison creates a mysterious and enchanted world pulsing with stories and secrets. Always the teacher, Morrison uses the literary techniques of estrangement and defamiliarization to expand the boundaries of our comfort zone, urging us to let go of many of our conventional reading strategies and allow the music of words to wash over us. Gradually, we become okay with not knowing: reveling in, rather than trying to explain away, the mystery.

The novel focuses on the friendship of Nel and Sula, two “solitary little girls,” who first met in dreams. Morrison writes,

“Because each had discovered years before that they were neither white nor male, and that all freedom and triumph was forbidden to them, they had to set about creating something else to be. Their meeting was fortunate, for it let them use each other to grow on. Daughters of distant mothers and incomprehensible fathers… they found in each other’s eyes the intimacy they were looking for” (52).

Their grand life experiment, their artform, was friendship: living for each other—for that “rib scraping” laughter (98)—and not for the mothers or the teachers or the men or the townspeople who demanded their attention. Sula protected the two from bullies (54-55) and, upon learning that her mother loved but did not like her, it is Nel who wraps Sula up in her arms.

As scholars like Monique Morris and Saidiya Hartman have shown, we live in a society characterized by the excessive disciplining of Black girls—one that is quick to tell them how to behave, what to want, what to pay attention to, and to punish them when they don’t conform. But Nel and Sula resist these rules by living for each other and according to their whims and fancies. They shared what Morrison calls a sense of

“adventuresomeness… and a mean determination to explore everything that interested them, from one-eyed chickens high-stepping in their penned yards to Mr. Bucklan Reed’s gold teeth, from the sound of sheets lapping in the wind to the labels on Tar Baby’s wine bottles. And they had no priorities” (55).

To live with no priorities—refusing to put religion, or education, or the family, above one’s own desires—is portrayed here not as ruthless self-interest but as a radical political act. Amidst a racist and patriarchal society that systematically devalues the lives of Black girls and pits women against one another in competition for men’s hearts, Nel and Sula refuse this logic altogether, exploring instead the transgressive force of female friendship.

I am hardly the first to take up this theme of female friendship in the novel. Morrison herself describes its central question:

“What is friendship between women when unmediated by men?”

Since its publication in 1973, scholars such as Susana Morris, Alisha Coleman, and Elizabeth Abel have analyzed Morrison’s powerful depiction of this girlhood friendship.

Traveling back to my own college classroom, the stories of these women—their experiments, trying to wrench freedom from the societal constraints of racism and sexism—raised new questions. In On the Road, were Sal and Dean’s adventures enabled by the fact that they were white men? Would Black women have been able to drive across the country as carelessly and unthreatened as Kerouac’s protagonists? In every provisional community of moment Dean and Sal established in a Louisiana Bayou, an apartment in the Village, a monastic retreat in Berkeley, why were women always the ones cooking their meals or left behind altogether to take care of the children? Might Black women like Nel, Sula, Eva, and Hannah have wanted to abandon everything—dancing and drinking in ecstatic evenings that melt into mornings—knowing always that they’d be taken care of? Toni Morrison taught me to ask these questions.

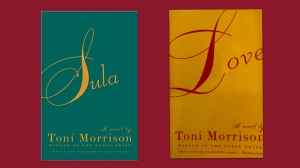

If I had more time, I would talk about the friendship between Heed Cosey and Christine that is at the heart of Morrison’s later novel, Love. What I love about this novel is that its premise —the death of charismatic, powerful patriarch Bill Cosey—becomes little more than a plot device that allows the beautiful complexities and vicissitudes of female friendships to come into full relief.

Morrison’s depictions of these female friendship have taught me that patriarchal society fears what women are capable of achieving when they work together in collaboration, rather than competition. Society is so fearful, in fact, that it tries to sell us the idea, over and over again, that marriage (and specifically, heterosexual marriage) is all that matters. As reality T.V. shows like The Bachelor remind us, week after week, women are supposed to compete with each other for the love and affection of men. And even when those dynamics are reversed, say, in The Bachelorette, where multiple men compete for a woman’s heart, it is the romantic, heterosexual relationship between a man and a woman that narratively prevails over the infinite friendships that I’m certain must form when you put thirty people in a house together for six weeks.

Nel and Sula’s friendship is one of stunning singularity that has, almost paradoxically, given me new ways of seeing the female friendships in my own life. Like Sula and Nel, I have seen romantic relationships fray the once-sacred bond between girlhood friends. But I’ve also experienced the unexpected pleasure of making female friends later in life, recognizing how much we have yet to explore together through stories, laughter, teaching, activism, passing books back and forth, giving feedback on each other’s writing. Amidst a society that tries to convince us that only marriage matters, Morrison reminds us that romantic partnerships are one among the many kinds of relationships that constitute a vibrant, joyous, and fulfilling life.

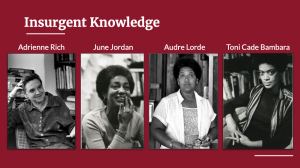

Morrison’s work has also shaped my research. Currently, I’m writing a book, tentatively titled Insurgent Knowledge, that looks at the relationship between writing, teaching, and educational activism in the work of four famous authors: Audre Lorde, Toni Cade Bambara, June Jordan, and Adrienne Rich. In 1968, at the height of the Women’s Movement, the Civil Rights Movement, the Black Power Movement, and protests against the Vietnam War, these authors—four of the most important writers of the twentieth century—were teaching down the hall from one another at Harlem’s City College. While these figures are most often studied for their writing, I position them as educators who developed teaching practices organized around social justice and as activists who advocated for free, high quality, public education for all.

While Morrison is not one of the teacher-poets I explicitly analyze, she was in conversation with all four of these writers, especially through her work as an editor, and her ideas about female friendship have shaped my project. Often, when we think of a scholarly book on four authors, we might imagine that its method is comparative: for instance, comparing Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich’s classrooms and perhaps evaluating whose teaching approach was more successful than the others. But Morrison’s ideas about what women are capable of when they work together—when they understand each other as allies, collaborators, and co-conspirators—is at the heart of this book, and the work that I hope it does in the world. Rather than comparing these teacher-poets, I aim to paint a picture of them in conversation, dialogue, and collaboration with each other, and as part of a larger movement in which teaching and writing were understood as crucial for social change.

Nel and Sula. Heed and Christine. I carry these women with me, wherever I go. Their friendships—Morrison’s friendships—remind us always, that the bonds among women are some of the most transgressive, transformative, and electrifying that exist.